1 Art Makes Use of Imagery That Departs From Recognizable Images Within the Natural World

five.iii: SYMBOLISM AND ICONOGRAPHY

- Page ID

- 10138

Symbolism refers to the apply of specific figural or naturalistic images, or abstracted graphic signs that hold shared pregnant within a grouping. A symbol is an image or sign that is understood by a group to stand up for something. The symbol, even so, does non have to have a straight connexion to its meaning. For example, the letters of the alphabet, which are abstract graphic signs, are understood past those who use them to have private sounds and meanings. The users have assigned meaning to them, as letters have no meaning in and of themselves. An example of a naturalistic image is a rose, which in most Western civilizations symbolizes dear. When one person gives a rose to another, it is a symbol of the love the person feels.

Iconography is the broader written report and interpretation of discipline matter and pictorial themes in a work of fine art. This includes implied meanings and symbolism that are used to convey the group's shared feel and history—its familiar myths and stories. Iconography refers to the symbols used inside a work of fine art and what they mean, or symbolize. For case, in different cultures a serpent may represent evil, temptation, wisdom, rebirth, or the circle of life. A depiction of a serpent in a scene with Adam and Eve has specific meanings for those of the Christian faith or others who understand the ophidian stands for temptation within the context of that subject or story. In Chinese culture, still, a snake represents the power of nature and is said to bring good fortune to those who practise the ophidian'southward restraint and elegance of movement.

5.three.1 Changes in Meaning of Symbols and Iconography

While a symbol might take a common meaning for a certain group, information technology might be used with variations by or hold a different significance for other groups. Let us use the instance of a cross. At its core, a cross is a simple intersection of vertical and horizontal lines that could refer to the coming together of angelic and terrestrial elements or forces or could lend itself to other variations of meaning. The cantankerous most frequently associated with Christianity is the Latin Cross, with the long vertical bar intersected by a shorter horizontal i believed by many to be the course of the cross upon which Jesus Christ, the cardinal figure of the organized religion, was crucified. (Variants of the Cross: http://wpmedia.vancouversun.com/2010...6.crosses1.png) But its simplicity of formulation lends itself to various other readings, equally well, and in pre Christian use it was related to sacred and cosmic beliefs.

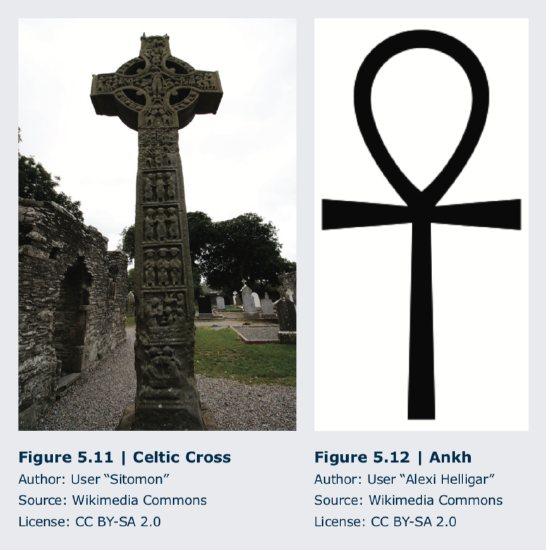

Within Christian usage, the cross has taken a great number of unlike of forms, including the equal-armed Greek Cross, favored by the Byzantine Christians; Celtic crosses, with a circular addition to the crossing; Ten'due south and upside-down crosses associated with specific Christian martyrs, individuals who died for their faith, on such instruments of torture; and many others. In art, nosotros might see them as uncomplicated flat graphic works, or decorated in two-dimensional renditions, or as fully adult 3-dimensional interpretations, like the numerous grave markers in Irish gaelic cemeteries, where they are further embellished with intricate motifs and iconographic depictions of Bible stories. (Figure 5.xi)

The Ankh, another cantankerous form, with a looped handle, seems to take been devised by the ancient Egyptians as a symbol of the life-giving power of the Sunday. (Figure 5.12) It was one of the numerous pictographic symbols they used both as a split sign and as function of the hieroglyphic system of writing they developed.

Clearly, many other symbols have various meanings, specially when they are represented as more than abstruse graphic signs. To read their implications in any detail application volition require your considering where information technology was made and for what specific purposes, as well equally how it might take been adopted and turned to different apply at that time or later. Sometimes the shifts in meaning may be radical, as in the grade of the swastika, an aboriginal sacred sign used in many dissimilar cultures, including India and others throughout Asia, as well as the Well-nigh East, and Europe. (Figures v.13, 5.14, and 5.15) Information technology has historically been a very cheering sign with implications of adept fortune and positive movement, and was therefore adopted for the ground plan for Buddhist stupa worship centers. Of class, in the twentieth century, its appropriation by the Nazi Party equally a symbol of the superiority of the Aryan heritage led to very different and at present generally negative connotations.

Iconography is oft more specific and definitive, with concrete reference to world experiences and, beyond that, to some course of narrative for the grouping involved. Over again, assay of the pictorial form requires examination of the con- text in which the artwork was created. Nosotros can and must look at the underlying narrative, simply, as we shall discuss in the next several chapters, the pictorial expressions evolve both independently of the narrative sources and in response to narrative and artistic change.

For example, Christians (more than specifically that branch at present known as Roman Catholics) debated the "truthful nature" of the Virgin Mary, the Mother of Jesus Christ. Among the points of debate was whether Mary was bodily in Sky with her Son or whether she had to wait until the cease of time when the whole of flesh would experience bodily resurrection, that is, at the time of the 2d Coming and the Last Judgment, when everyone would accept their lifetime of deeds assessed for purposes of learning whether they would spend eternity in Heaven or Hell. These Christian ideas are among those a great amount of art has been devoted to over fourth dimension.

To illustrate, we tin look at differences betwixt ii works nearly Mary and her place and part in Heaven that appeared in church relief sculpture during the 12th and thirteenth centuries. These differing ideas focused on the implied elevation of Mary to a divine status, or to her not being seen as divine herself, in which case, the true-blue needed to keep a view of her every bit existence in a more than subordinate or secondary status. The questions included consideration of Mary as the "Queen of Heaven," who might be ruling alongside her son. At Senlis Cathedral (1153-1181) in France, she was depicted as manifestly a co-ruler with Christ, but ensuing theological word took issue with this possible over-elevation. (Figure 5.16) Then, while the renditions of Mary every bit the celestial queen continued in popularity, they made it articulate that she was just considered to exist there at the behest and will of Christ. This can be seen at Chartres Cathedral in France, where she bows her head to Jesus. (North Portal of Notre-Dame Cathedral: https://www.bluffton.edu/~sullivanm/ chartresnorth/cportal.html)

What nosotros meet here, again, is that our full analysis of the artworks we encounter needs a complex approach that includes a diversity of visual clues and a wide range of research on the contextual details of its creation and use. In dissimilarity to the longstanding assertion that "beauty is in the center of the beholder," the appropriate interpretation co-ordinate to the intended symbolism and/or iconography must take the lodge, culture, and related circumstances into account to accurately reflect its intended meaning or original meaning for viewers. We will be exploring these ideas in greater detail in the adjacent several chapters.

v.3.2 Symbolism, Iconography, and Visual Literacy

Symbols like the cross or the swastika will just accept shared meaning for those who agree upon and affirm a specific estimation, which can exist positive or negative for any particular grouping of people. This specific meaning in symbols is always going to be the instance for viewing of whatever visual expression, whether in simplified graphic sign form or a more detailed pictorial rendition. Additionally, the viewers must besides often have some measure of instruction well-nigh how to view a particular work and then they can sympathise its pregnant more fully.

Also noteworthy is that members of any grouping use art equally a means of sharing ideas and sentiment, also every bit for expressing and teaching credo. While the didactic uses of art have ofttimes been discussed in terms of instruction for the non-literate, we should recognize that the meanings of pictorial content and the tools used to create the picture must be learned as well. The apparent superficial meanings that are evident through unschooled visual test practise not produce the level of comprehension bachelor in a more than fully developed illustration of a tenet of a organized religion, political message, history lesson, or nautical chart or graph of economic trends. So "visual literacy" should be considered a skill related to verbal and reading literacy for any didactic role. Only members of a group who have been led to empathize and perceive the underlying principles will know how to "read" an illustrated message.

Also noteworthy is that members of any grouping use art equally a means of sharing ideas and sentiment, also every bit for expressing and teaching credo. While the didactic uses of art have ofttimes been discussed in terms of instruction for the non-literate, we should recognize that the meanings of pictorial content and the tools used to create the picture must be learned as well. The apparent superficial meanings that are evident through unschooled visual test practise not produce the level of comprehension bachelor in a more than fully developed illustration of a tenet of a organized religion, political message, history lesson, or nautical chart or graph of economic trends. So "visual literacy" should be considered a skill related to verbal and reading literacy for any didactic role. Only members of a group who have been led to empathize and perceive the underlying principles will know how to "read" an illustrated message.

For instance, we tin can await at the Ritual Vase from Warka (today Iraq) or the Seven Sacraments Altarpiece by Rogier van der Weyden. (The Warka Vase: http:// dieselpunk44.blogspot. com/2013/08/the-warka- vase.html) (Figure v.17) One could likely place the bones pictorial content of either piece of work, but further knowledge would be needed to analyze them further. If you were a member of the intended audition, you might take a scrap more insight into what each creative person had created in pictorial terms, but fifty-fifty the initiated viewer would likely take a limited "reading" of the work.

In the case of the Ritual Vase from Warka, even if you had lived in aboriginal Sumer and had been a devotee of the goddess Inanna, you lot would probable demand farther instruction about how the carvings on the unlike registers of the vase were arranged to show the cosmological conception of the created world. That is, one starts at the lesser with the primordial globe and waters, moves to the plants and animals higher up them drawing sustenance so that they could exist harvested and herded past the humans, who then offer office of their gleanings to the goddess serving them from the temple equally seen in the upper realm of the center photo. This design would be farther explained as a neatly hierarchical arrangement, in which the levels of the created earth were presented in different sizes, according to their relative importance. Boosted meanings could be layered upon this cursory explanation with repeated teaching occasions and viewings.

The Seven Sacraments Altarpiece was painted past Rogier van der Weyden in a region and an era of tremendously complicated iconography: Flanders during the Late Gothic/Northern Renaissance catamenia. The presentation here includes detailed pictorial description of each of the vii sacraments that marked the stages and stations of Christian life. This symbolism again developed over time, and often in response to theological writings that informed the creative person and the viewer most specific meanings. The written sources are detailed and circuitous, with the pictorial rendition richly reflecting what the well-instructed Christian would know about these important rituals and their effects.

The larger key panel of the triptych, or three-role, format was used by the creative person to emphasize the Crucifixion equally the ascendant overarching event that is related to each of the sacraments. Additionally, he provided angels with scrolls to identify them as if speaking to the viewer. Then, hither the letters are both pictorial and inscribed, and the iconography is a complex plan that relates all these ritual events to the whole of the Christian life and faith. Truly, the viewer must be an initiate to discern the meanings backside all the symbolism or a scholar to discover them. Nonetheless, even the casual or uninitiated can read much of what is nowadays in the painting and can identify both familiar elements and those that might lead you to further investigation. This is often the task and the path in interpretation of iconography in art.

five.3.3 Symbolism and Iconography in Mythology and Storytelling

From early on, art contained expressions of mythical accounts that people shared well-nigh their beliefs and ways of living. From the time of the first groovy civilizations, for example, in Egypt, the Nigh East, China, Nippon, and India, artwork related to the stories of the people. The degree to which whatsoever contemporary written sources confirm these interpretations varies, but that these myths had unremarkably understood meanings for the people for whom they were fabricated is confirmed by both their frequent appearance and their apparent places in their civilization'south artistic traditions, sometimes over centuries. Artistic iconographic traditions therefore prove stiff relationships to beliefs and practices known from written sources—although written documentation sometimes does not appear until afterwards times.

Because early stories were ofttimes passed forth through oral tales, we do not always have a literary tape of them until later times, even after the ideas had been expressed symbolically in pictorial art. An example of this symbolism may be constitute in the rich hoard (a collection of objects) known as the Sutton Hoo Send Burying, found in England and deriving from the early Eye Ages era known as the Migration menses (300-700 CE). Although the wooden ship itself has disintegrated, the burial hoard it contained provides details that ostend and broaden our incomplete understating of the adventurous societies of that time and their behavior well-nigh needs for the afterlife. The diverse objects besides lend certain insights into the epic tales of such warrior kings as Beowulf, whose story seems to have been a long-standing oral tradition, one possibly re-told for centuries before being commit- ted to written form. The lavish ornaments, such as this belt buckle and purse encompass, requite visual testimony to the tales of dragons and heroes similar Beowulf through their expressive and intricate patterns and rich materials. (Figures 5.18 and v.19) The fine metalwork on the purse encompass is cloisonné,which is created by affixing aureate or metal strips to the back surface, making compartments, that are filled with powder (in this case, basis garnets) and heated to 1,400-1,600 degrees F.

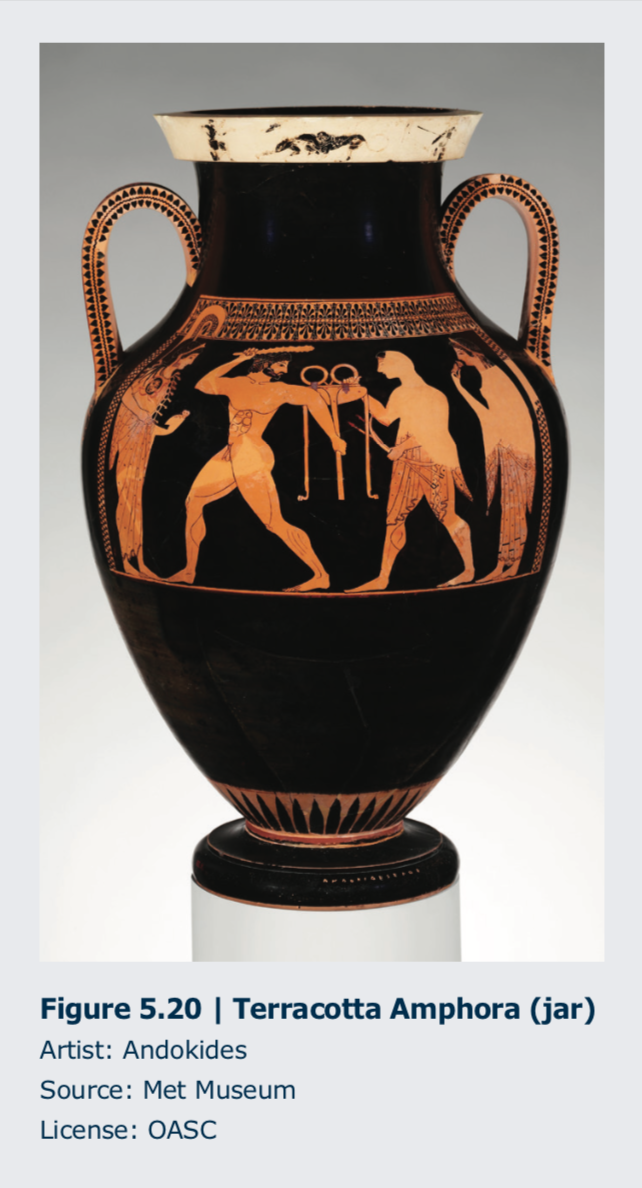

The art of ancient Hellenic republic often showed great concern with the stories of Greek mythology as well. Tales of the gods and warriors abound, including those about great physical or intellectual contest, such as the well-known struggles of Herakles (known every bit Hercules under the Romans) 1 of which is seen on this amphora. (Effigy 5.20) Such tales were very familiar, and viewers were expected to supply the details of the remainder of the story through the parts that were shown. However, the practiced creative person can enliven the presentation of the figures with posture, gesture, expression, and such symbolic props as the gild and the tripod Herakles holds.

The art of ancient Hellenic republic often showed great concern with the stories of Greek mythology as well. Tales of the gods and warriors abound, including those about great physical or intellectual contest, such as the well-known struggles of Herakles (known every bit Hercules under the Romans) 1 of which is seen on this amphora. (Effigy 5.20) Such tales were very familiar, and viewers were expected to supply the details of the remainder of the story through the parts that were shown. However, the practiced creative person can enliven the presentation of the figures with posture, gesture, expression, and such symbolic props as the gild and the tripod Herakles holds.

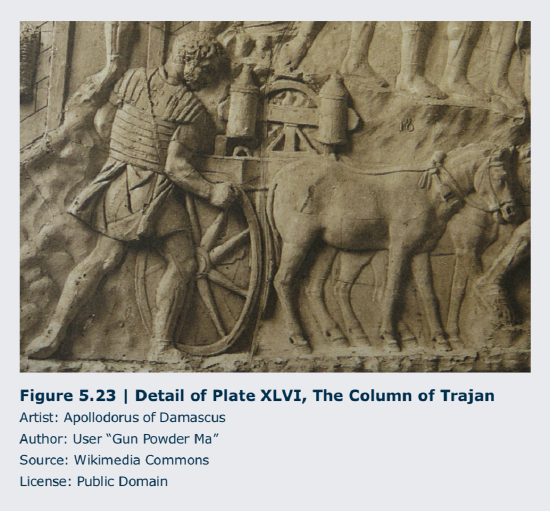

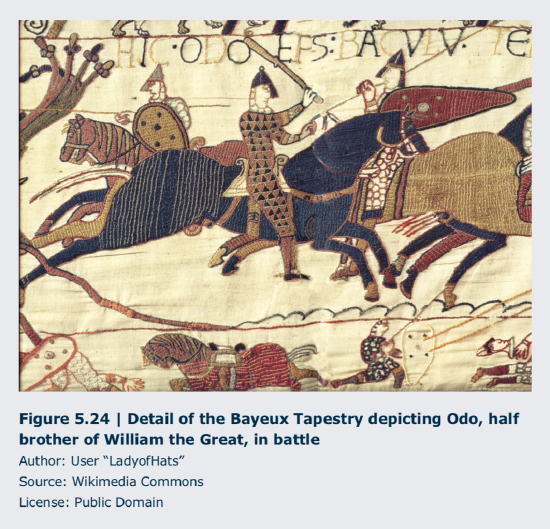

Equally with literary accounts, the artworks associated with historical and legendary events often include a very wide range of symbols and imagery to assistance convey ideas. These range from mundane details to one thousand historical moments, every bit in the Column of Trajan, nearly 100 anxiety in height, which commemorates the military campaigns of Roman Emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 CE) against the Dacians (101-102 and 105-106 CE) in 155 scenes. (Effigy 5.21) Or equally appear in the Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered fabric 230 feet in length that pictorially recounts the events of the Norman Invasion and Battle of Hastings in 1066. (Figure 5.22) Each of these works shows decisive points in their respective historical events in regular army operations and in the details of the hard work involved in preparing for battle. (Figures v.23 and 5.24) In this way, they provide u.s. with glimpses of everyday life in the respective eras alongside specific details about the particular campaigns, the cultures in which they were meaning, and the individuals who were key players in the historical events. The details of arms and armor, organized troops and cluttered fighting, building of defensive structures and devices, moments of victory and defeat, and innumerable other items and activities—all are individually and collectively efficient means of recounting the evolution of the events which, in each of these works, is dramatically developed across a long scrolled compositional field that further emphasizes the lengthy narrative each one progressively disclosed.

Like many works of public art of the Roman Imperial era, the column glorifies not simply Trajan (the base of the column was designed to incorporate his ashes) and his deeds, but likewise the ideas of imperial rule, the role of conquest in expanding the Empire, and the skilled work of Roman soldiers in battlements and tactics. By contrast, the Bayeux Tapestry has more accent on the actual tumultuous battle scenes replete with mounted cavalry in chain mail and elaborate helmets but it also includes a great deal more than sense of historical con- text: events leading upwards to the 1066 Boxing of Hastings later the death of King Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066) and his burial in the newly refurbished Westminster Abbey he had adopted equally his regal church. Both of these works also include inscriptions that explicate ideas and events, every bit well as serve to further present the political messages near the battles presented on the tapestry in a sort of scene-by-scene narrative again, for each, underscoring the relationships between literary and pictorial presentations of ideas.

v.three.four Exploring Symbolic and Iconographic Motifs

v.three.four Exploring Symbolic and Iconographic Motifs

Such items as arms and armor are obvious sorts of symbols that conspicuously depict their purposes, but much symbolism that nosotros see in other artworks has more veiled and variable meaning. Such uncomplicated items as flowers and candles can exist used in very complex ways in pictures that carry various meanings, thus requiring careful written report and fifty-fifty deep research in order to discern their implications in a item work.

For case, the Merode Altarpiece by Robert Campin (c. 1375-1444, Belgium) depicts the Christian story of the Declaration to the Virgin Mary by the Angel Gabriel that she will become the Female parent of Christ, the son of God. (Figure v.25) This work is full of symbols that take been widely studied to discern and translate their messages. The lilies are mostly interpreted to symbolize the purity and virginity of Mary in other pictures, though, they might have other meanings, including reference to death, resurrection, birth, motherhood, or other events or conditions. Within this one work, the utilize of the candle, just extinguished with a trail of fume, is given several different meanings by diverse viewers and scholars. It might prove the moment of acquiescence, when Mary agrees to bear the Christ child, in which God takes human class. It has as well been read as a foreshadowing of Christ'south decease, of human expiry in full general, and of the fleeting nature of life for all.

In the time and place of the altarpiece's creation, symbolism in paintings was particularly apt to be rich and varied, offering the viewer/believer a lot to see and to contemplate farther. In this way, if the symbols could exist read in different ways, they could then provide ongoing stimulus for meditative reflection on the diverse levels of meaning.

For case, the Merode Altarpiece by Robert Campin (c. 1375-1444, Kingdom of belgium) depicts the Christian story of the Declaration to the Virgin Mary by the Angel Gabriel that she will go the Mother of Christ, the son of God. (Figure 5.25) This piece of work is full of symbols that have been widely studied to discern and interpret their messages. The lilies are generally interpreted to symbolize the purity and virginity of Mary in other pictures, though, they might have other meanings, including reference to death, resurrection, birth, motherhood, or other events or conditions. Inside this one work, the employ of the candle, just extinguished with a trail of smoke, is given several unlike meanings by various viewers and scholars. It might show the moment of acquiescence, when Mary agrees to bear the Christ child, in which God takes human class. It has also been read as a foreshadowing of Christ's expiry, of human death in full general, and of the fleeting nature of life for all.

In the fourth dimension and place of the altarpiece's creation, symbolism in paintings was specially apt to be rich and varied, offer the viewer/laic a lot to meet and to contemplate further. In this way, if the symbols could be read in different ways, they could then provide ongoing stimulus for meditative reflection on the various levels of pregnant.

And some symbolic motifs, distinguishing features or ideas, carry dissimilar meaning in one context from what they might in another. Most symbols are non universal, although they frequently bear related meanings in diverse contexts. For instance, the sort of figure you lot might identify as an angel, that is, a winged creature with a human-like bodily class, has appeared in the art of many dissimilar cultures. They generally represent beings that can travel between the terrestrial and celestial realms, merely their more specific roles can vary widely, for expert or evil purposes. The Angel Gabriel, just seen in the Merode Altarpiece, was a messenger from God, co-ordinate to the Christian tradition. This motif was congenital upon the Jewish tradition of angels sent from God for bringing news or instructions, or intervening as needed. Islamic interpretations, likewise building on the same traditions, are like although the figural representation is less mutual in Muslim artwork.

And some symbolic motifs, distinguishing features or ideas, carry dissimilar meaning in one context from what they might in another. Most symbols are non universal, although they frequently bear related meanings in diverse contexts. For instance, the sort of figure you lot might identify as an angel, that is, a winged creature with a human-like bodily class, has appeared in the art of many dissimilar cultures. They generally represent beings that can travel between the terrestrial and celestial realms, merely their more specific roles can vary widely, for expert or evil purposes. The Angel Gabriel, just seen in the Merode Altarpiece, was a messenger from God, co-ordinate to the Christian tradition. This motif was congenital upon the Jewish tradition of angels sent from God for bringing news or instructions, or intervening as needed. Islamic interpretations, likewise building on the same traditions, are like although the figural representation is less mutual in Muslim artwork.

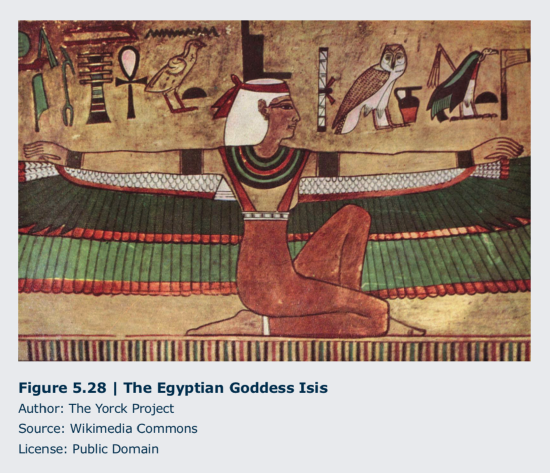

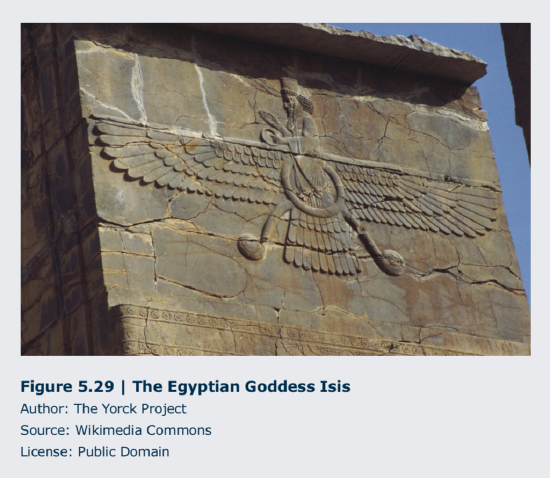

Prior to such figures, winged creatures known as Nikes were depicted by ancient Greek and Roman artists to prove a moment of victory, sometimes, as is the case here, further symbolized by the laurels of a fillet, a band wrapped around the head, or laurel wreath. (Figure v.26) These winged figures were sometimes gods or goddesses. The genie figures that adorned palace walls in the ancient Nigh Eastward, including horses, bulls, lions, and other animals, were also winged to bear witness their superior and sometimes god-similar powers or origins. (Effigy 5.27) Other examples include the goddess Isis of an- cient Egypt, and the Persian god Ahura Mazda. (Figures 5.28 and 5.29)

Some other fix of prominent Christian iconographic motifs are the winged symbols which often stand for the 4 Evangelists in art: Matthew is the winged man or angel; Marking, the winged lion; Luke, a winged ox; and John, an eagle. (Effigy v.30) At the same time they refer to four fundamental events in the life of Christ: the Incarnation, Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension. Interpretations of these evangelist symbols are rooted in the Onetime Testament Vision of Ezekiel and the New Testament Volume of Revelation, every bit related by the writings of St. Jerome in the fifth century CE. They accrued additional iconographic details over the centuries, with implications of their status as the special creatures who surround the celestial throne of God again, signifying that the wings facilitate movement between the realms traditionally ascribed to a deity, a god or goddess, and divinely related creatures. This use of wings clearly reflects human contemplation of the abilities that birds accept to defy gravity and to express artistically the lofty aspirations of the earthbound.

Another frequently used iconographic motif that appears across the ages and across cultures is the halo, commonly a circular area of low-cal actualization behind the head of a person or creature. One example is the halo that appears behind the heads of Christ and the symbolic winged creatures in Figure 5.30. Notation that Christ's halo has a cross form embedded in it, and his entire torso is surrounded past a circle of light (made up of four arcs) known as an aureole or mandorla. Such devices, in many related forms, indicate a radiance that surrounds certain figures, showing their sanctity, divinity, or divine favor. It indicates their aura of holiness, with implications of their being infused with warmth, inflamed with divinity or with divine love. In some of the Asian versions, notably Hindu or Buddhist, the radiance is literally comprised of flames.

Frequently seen, as well, are such items every bit crowns, thrones, regalia like scepters, garments like official capes, monks' robes, or uniforms of all varieties indications of a person'south belonging to a specific group, class, or office that lead the viewer to identify some specific aspect of who the person might exist and what role they have in the delineation. The positioning of figures relative to one some other should too be read in order to discern meaning, interactions, relative rank, and other implications. The types of garb, accompanying items, and positioning often relate the message to a specific time and place by giving historical and cultural context through details of style or motifs used.

For instance, on the stele depicting his victory over the Lullubi, the Akkadian ruler Naram Sin (r. c. 2254-2218 BCE) wears a horned helmet and is much bigger than the men around him. (Figure 5.31) He ascends the mountain equally his enemies beg for mercy under the watch of astral deities, and that shows his relationship to them as the source of his power and right to rule. In the Ghent Al- tarpiece by Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441, Belgium), we tin can also come across a diverseness of such motifs: Christ, wearing the papal ti- ara as a crown; Mary, richly dressed and humbly reading; and John the Baptist, in his garment of penitence, and preaching. (Figure 5.32) Adorned with jewels and golden on his clothing, the throne on which he sits, and the crown at his feet, Christ is here being shown as the king of Heaven as well as Earth.

For instance, on the stele depicting his victory over the Lullubi, the Akkadian ruler Naram Sin (r. c. 2254-2218 BCE) wears a horned helmet and is much bigger than the men around him. (Figure 5.31) He ascends the mountain equally his enemies beg for mercy under the watch of astral deities, and that shows his relationship to them as the source of his power and right to rule. In the Ghent Al- tarpiece by Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441, Belgium), we tin can also come across a diverseness of such motifs: Christ, wearing the papal ti- ara as a crown; Mary, richly dressed and humbly reading; and John the Baptist, in his garment of penitence, and preaching. (Figure 5.32) Adorned with jewels and golden on his clothing, the throne on which he sits, and the crown at his feet, Christ is here being shown as the king of Heaven as well as Earth.

v.3.v Metaphorical Meanings

The metaphorical meanings of specific artworks too depend upon a certain level of viewer noesis and insight. A metaphor is a figure of speech in which i thing symbolically stands for another, perhaps unrelated, matter or idea.

In 1550 Chairs Stacked Between 2 City Buildings by Doris Salcedo (b. 1958, Columbia), nosotros meet a metaphorical treatment of life change. (1550 Chairs Stacked Betwixt Two City Buildings, Doris Salcedo: http://world wide web.mymodernmet.com/profiles/...southward-salcedo-1550 chairs-stacked) It is a view of displacement resulting from a 1985 insurgence in her Colombian homeland that left many migrants displaced or dead, as well equally similar catastrophic events in locales across the world. The jumbled mass of furniture alludes to the upheaval of lives that are overturned by mass violence and terrorism, oftentimes of those already without roots, community, or stable lifestyles. The victims, frequently bearding and relatively invisible in the site of such a revolt, nonetheless left some hints of their presence in the cluttered remnants of their fleeting existence, in a identify where they had established so footling sense of their individual identities. Her metaphorical expression gives a probing glimpse of the devastation such events have wrought around the world.

Source: https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Art/Book%3A_Introduction_to_Art_-_Design_Context_and_Meaning_(Sachant_et_al.)/05%3A_Meaning_in_Art/5.03%3A_SYMBOLISM_AND_ICONOGRAPHY

0 Response to "1 Art Makes Use of Imagery That Departs From Recognizable Images Within the Natural World"

Post a Comment